Category Archives: NEWS DESK

Clean Birthing Kit Assemble Day at St Stephens Episcopal Church

Image

Date: Saturday, September 20 2014

Time: 9 am- 12 noon

Venue:St Stephen’s Episcopal Church,Coconut Grove

3439 Main Hwy

Coconut Grove,Florida

305-445-2606

Cost Per Kit:$7.00

Cost To Register Team:$70.00

Team:10 persons

T Shirt.$15.00

Team Goal: 50 Clean Birthing Kits.

Name your team.

Goal for the Day: 2000 clean birthing kit for the Mothers in Africa

This is where they are delivering their Babies

If you prefer to donate by mail, please send a check to :

Footprints Foundation 4000 Ponce Deleon Blvd. Ste 470,Miami Fl 33133

TEAMS

BOOM Committee

Barnes Circle

One Grove Foundation

Lorna Owens. Amazing Grace

Dr. David Farcy. Team Farcy Works.

Michelle Menendez. Robin’s Angel

Hialeah Rotary. TEAM HIALEAH MIAMI SPRINGS ROTARY

Hope Powell

Maria Estevez

Carolyn Johnson

Susan Karms

Women’s Club,Coconut Grove.

Robbie Bell

THE EVENT

Ebola

Image

The World Health Organization said Friday the West Africa Ebola outbreak has killed more than 3,000 people and infected more than 6,500.

The U.S. is sending 3,000 military personnel to build 17 treatment facilities in the weeks ahead, but there’s only a handful there now.

The military eventually hopes to provide 1700 new beds for patients and train up to 500 local health care workers each week.

Dr. Paul Farmer co-founded Partners in Health, an organization that helps build health care systems in developing nations. He was recently in Liberia and met with President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

What it will take to end the Ebola epidemic

There seems to be a disconnect in numbers of hundreds of thousands of people being infected, and the possibility of 1700 more treatment beds.

“Seventeen-hundred more treatment beds does not seem like a lot to me, when you’re talking about a potential need of that scale, so I think there is a mismatch in the math,” said Farmer.

But even if there were enough supplies, Farmer says much more needs to be done to bring the Ebola epidemic under control in a region with broken health care.

“To stop it you have to do two things at once. You have to respond to the emergency, the crisis,” said Farmer. “But also to build a really strong public health system that can go all the way from villages and communities to hospitals. That’s a tall order.”

New therapies and vaccines are being developed. But they won’t be available for many months, says Ebola researcher Thomas Geisbert of the University of Texas Medical Branch.

Dr. Paul Farmer with Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

“The goal at this point is to contain it, isolate, quarantine the affected people,” said Geisbert. “That’s the more important thing that can be done right now, more so than the vaccines or the treatment. I’m not sure that they will be available really to manage this current outbreak.”

“We know how to prevent Ebola,” said Farmer. “What we need to do is apply that knowledge to building health care systems and to financing. We can do that.”

Farmer believes the mortality rate can be dramatically lowered with modern treatments like IV fluids.

He said an improved survival rate would help convince frightened victims to seek help rather than staying at home, where they often spread the virus to caregivers.

© 2014 CBS Interactive Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Study Suggests Reason Why Black Mothers Breastfeed less than White Moms

Image

When it comes to breastfeeding, a persistent racial disparity exists: Black mothers have lower breastfeeding rates than white mothers. In 2010, 62 percent of American black babies were breastfed at birth, compared to 79 percent of white babies. A new study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may provide some insight into a possible cause of this discrepancy.

Turns out, certain hospitals that serve black communities are failing to fully support breastfeeding. In its most recent Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the CDC reported that hospitals may play a role in the racial discrepancies. The CDC found that facilities in zip codes with more than 12.2 percent black residents were less likely than hospitals in zip codes with fewer black residents to meet five of 10 indicators that show hospitals are supporting breastfeeding.

The CDC looked at the 10 indicators it identified in its 2011 Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC) survey. They include: educating mothers and health care staff properly, helping mothers initiate breastfeeding within one hour of birth and making sure not to give pacifiers or artificial nipples to infants. The researchers coupled these mPINC indicators with U.S. Census data to analyze 2,643 hospitals across the country. No other racial groups were studied.

Given that most babies in the United States are born in a hospital, the short time that a mother and a newborn spend there can have a long-lasting effect on breastfeeding, Jennifer Lind, who holds a doctor of pharmacy and was the lead researcher on the CDC study, told The Huffington Post.

“We’re not really sure all of the reasons why there’s this persistent disparity,” she said. “We know that maternity care practices play an important role in women being able to start and continue breastfeeding, so we wanted to look to see if maybe some of the disparities are starting in the maternity care time periods.”

The CDC found that facilities in zip codes with more than a 12.2 percent black population were much less likely to implement three specific mPINC indicators: helping mothers initiate breastfeeding early on (46 percent compared with 59.9 percent), having infants spend the majority of their time in the same room as their moms, or “rooming-in” (27.7 percent compared with 39.4 percent), and and limiting what infants eat or drink to only breast milk (13.1 percent compared with 25.8 percent).

“Hospital practices during that childbirth period have a major impact on whether a mother is able to start and continue breastfeeding,” Lind said. “So it’s very important that hospitals support mothers in their breastfeeding decisions and follow the recommended policies that have been proven to support breastfeeding.”

The CDC’s findings may contextualize the consistently lower rates of breastfeeding in the black community, as people are usually admitted to hospitals close to where they live, according to the CDC.

However, Pat Shelly, director of The Breastfeeding Center, an organization that promotes lactation education, said that the racial discrepancy may have more to do with socioeconomic factors than simply race.

“Education, money and family support are huge equalizers,” Shelly told The Huffington Post, citing breastfeeding education, access to high-quality healthcare and poor nutrition as possible factors that affect breastfeeding rates.

“All mothers really don’t have a true choice, so that’s really what we’re looking for, particularly amongst black women and particularly with our low-income sisters,” Kimberly Seals Allers told HuffPost Live yesterday in light of the second annual Black Breastfeeding Week.

Allers, a breastfeeding advocate who organized the awareness week specifically for black mothers, said that social stigma may play a role as well. She said she was told “breastfeeding is for poor people” and questioned about whether her baby was eating enough when she started to breastfeed her first child. She also cited formula marketing strategies, myths like breastfeeding leads to breast cancer (it actually has been shown to lower the risk), and a lack of black mothers in breastfeeding marketing and education materials as hindrances to breastfeeding in the black community.

The American Academy of Pediatrics considers breastfeeding and human milk the“normative standards for infant feeding” and recommends exclusive breastfeeding for a baby’s first six months. But the lower rates of breastfeeding in the black community remain an unsolved issue. The CDC is currently funding a three-year project with the National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality that aims to increase breastfeeding at 89 hospitals in low-income areas.

Shelly, like Allers, emphasized that hospitals can only do so much before other factors come into play, like preconceptions about breastfeeding, family influence, professional support and a need for a mother to return to work soon after the baby is born.

“There are times that the hospital can be doing its job, but what about afterward, once breastfeeding is really getting started?” Shelly said.

Watch the conversation on HuffPost Live Here

Around the Web

Hospitals Less Likely To Encourage Black Mothers To Breastfeed

Why Do Black Women Breastfeed Less?

Praeclarus Press Proudly Supports Black Breastfeeding Week (August 25-31 …

Racial Disparities in Breastfeeding

Researchers call for new African-American mothers, grandmas for breastfeeding …

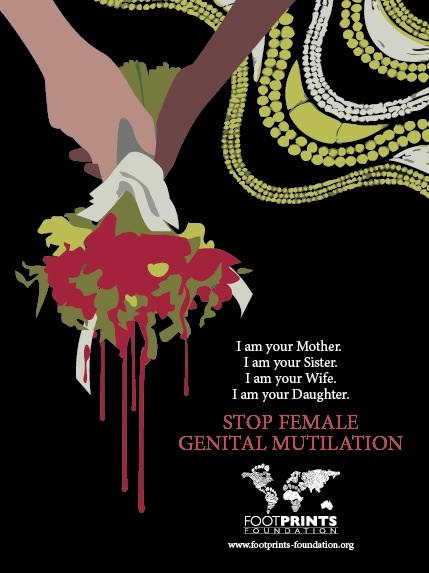

THE FIGHT AGAINST FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION

Image

If you prefer to donate by mail, please send a check to :

Footprints Foundation 4000 Ponce Deleon Blvd .

Ste 470 Coral Gables Florida 33146

HUMAN RIGHTS

The fight against female genital mutilation

Between 130 and 150 million women are victims of genital mutilation – most of them are Africans. Now, doctors, teachers and social workers in Germany are increasingly being confronted by this practice.

Somalian Jawahir Cumar moved to Germany with her parents when she was a girl. Later, on a visit to her grandparents’ village when she was 20, Jawahir witnessed the funeral of young girl who had bled to death after being “circumcised.”

“And then I saw another case,” the now 36 year old says. “A pregnant woman was in labor. She had never been to a doctor, there was nowhere for her to get ultrasound in the area – the next hospital was 900 kilometers away, in Mogadishu. After the birth of the child, the woman was sewn up again.”

The midwife had overlooked the fact that the woman had been carrying twins, so she was still in pain. She was later transported to Mogadishu by car – a journey that took two days. And although she survived, the second twin died.

Severe health damage

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is currently practiced in 29 African countries, despite being illegal in some. It is usually done when girls are between the ages of four and eight – using varying instruments, ranging from razor blades, kitchen knives to broken glass and tin lids. And because these tools are used more than once, it also increases the risk of spreading diseases like HIV/AIDS and hepatitis.

Female genital mutilation includes procedures that intentionally alter or cause injury to female genitalia for non-medical reasons, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). These practices include partial or total removal of the clitoris, the removal of the labia and narrowing the vaginal opening by creating a covering seal to leave a small opening of about two to four millimeters.

About 15 percent of the women who have been cut (especially in Somalia and Sudan) have also undergone infibulation, which results in the vaginal opening being almost sealed completely.

“If the vagina is almost closed, urine and menstrual fluids can hardly be discharged and remain trapped as a result,” explains Dr. Christoph Zerm, a gynecologist who specializes in counseling and treating women who have undergone FGM.

“This creates an environment that is conducive for infections. It can cause severe illness in the urinary tract and even the kidney. The uterus, ovaries and the fallopian tubes can also get infected,” he adds.

And for these women, even urinating, which can take up to 30 minutes, is painful.

Raising awareness in Germany

Jawahir was just a girl when she was cut. As a result, she had to have several surgeries in Germany to reverse the infibulation. She wants to prevent other girls and women from having a similar experience. That’s why she founded “Stop Mutilation.”

“The immigrants that come here bring this problem with them. That’s what made me create this organization in 1996,” says Jawahir, who is now a mother of three.

An estimated 30,000 women living in Germany have been been subjected to FGM and 6,000 girls are at risk, according to human rights organization Terre des Femmes. Pressure from families in their countries of origin plays a big role.

“Mothers-in-law and grandmothers, especially, call all the time, write letters and send messages,” says Jawahir Cumar. And the message is always the same, “[they say] you have to cut your daughters! Or just bring them to us and we will do it,” she adds.

Jawahir visits kindergartens and advises teachers on how they can raise awareness about FGM. She also targets African immigrants in her advocacy work.

“Many of them don’t know that [female genital mutilation] is prohibited in Germany. They are shocked when they hear that they could lose custody for their children,” Jawahir says.

She was able to prevent 17 girls from getting being subjected to FGM last year.

Getting Africans to ban FGM

Somalian Fadumo Korn also talks about FGM with immigrant families from Somalia and other African countries. She warns them that it can result in a prison sentence or deportation.

“It only works from one African to another,” she says, because Europeans are often not seen as the right people to raise awareness in Africa.

“It is easy for me because I am also a victim. No one can tell me that genital mutilation isn’t bad,” Fadumo adds.

Together with Nala, an association in Frankfurt, she was able to convince 18,000 people from a community in northeastern Burkina Faso to publicly renounce FGM.

“We got support from the local imam and the head priest of the Christian community, as well as the chief of this region for our campaign. These three men stood up and told their community that FGM is forbidden,” Fadumo explains.

Even though religion is often used to justify FGM, neither Islam nor Christianity demand it of their followers. Fadumo believes it is important for religious leaders to clearly speak out against the practice to change tradition in their communities.

“Whether it’s Islam or Christianity, we use all religions to tell people, ‘Your God will be angry with you, if you circumcise his children,'” she says.

Re-education is key

Both Jawahir and Fadomo, and activists in Africa face major challenges in the fight against female genital mutilation. Women practicing FGM have to be re-educated and families have to be convinced to let their daughters grow up without being cut.

“Men have to learn than a woman who is not cut can also have children and make her husband happy,” Jawahir Cumar says, while adding that families also need to recognize the importance of education for their daughters.

But there’s still a lot of work to be done in Germany as well, says Jawahir, pointing to how long it took for forced marriages and “honor killings” to be regarded as a criminal offence and not simply as the customs of immigrants.

Gynecologist Christoph Zerm would like medical students to learn more about FGM, so doctors can provide better care to women who are affected.

DW.DE

IN FOCUS: Putting a stop to female genital mutilation

Author Mirjam Gehrke / es

Copied from DW

Amazon Smile. Shop Now

Image

RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES

Image

Footprints Foundation Opportunities for Research and Collaboration

The Foundation is involved in training the Skilled Nurses and

supporting “train the trainer” of the traditional birth attendants. The Foundation also provides clean safe delivery kits to TBAs in different regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The regions are Region 1- Bukavu,Urban; Region 2- Mwenga and Kamituga, Rural.

1- Baseline literature review of outcome indicators comparing programs that provide training to programs that provide supplies.

2- Compare standardized curriculum to curriculum led by in-country practitioners.

Look at outcome indicators by setting up a database:

1- Pre-term birth

2- Pre-eclampsia

3- Shoulder dystocia

4- Birth Defects

5- Birth anomalies

6- Hemorrhage

7- Referrals or transfers to higher acuity

8- Cesarean deliveries

9- Maternal Death

10- Neonatal Death

Curriculum evaluation

1- Competency testing of SKBAs, pre and post tests

2- Verbal testing for TBAs

SAVING LIVES WITH SMARTPHONES

Image

Louis Fazen, a doctoral candidate at the School of Public Health, is part of an international team of researchers that has been awarded a $250,000 grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for a project that uses smartphones to reduce infant and maternal mortality in Kenya.

Fazen, who is currently in his sixth year of the MD/PhD program and a student in the division of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases, is part of a research group that was recently awarded a Grand Challenges grant for its “Saving Lives at Birth” project.

Fazen and his colleagues will work with the Kenya Ministry of Health and a government-sponsored HIV-prevention program called the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare to train and support Community Health Workers (CHWs) to address a rising level of maternal and infant mortality. The grant funds the development of an information technology system that uses cutting-edge technology to foster rapid communication and feedback between mothers, their communities and their health care providers.

This Mother-Baby Health Network will use the phones to facilitate home- and group-based care through CHWs and to improve collective advocacy. It will rely on an electronic medical record system that can be sent directly to CHWs using smartphones, allowing women and their newborns to be correctly triaged for care.

“Addressing these health needs requires a rapid and efficient information management system that extends from health facilities to individual households, crossing over geographic and socioeconomic divisions,” said Louis, who currently lives in Eldoret, Kenya. It will, he said, provide communities with the information and communication tools they need to ensure that every mother and child has access to essential care at time of delivery and within the first 48 hours after giving birth.

Integrated with text messaging, the Mother-Baby Health Network will also be capable of notifying health care providers, alerting nearby GPS-tracked taxis within an emergency transport system, and activating a personalized community of advocates to mobilize local resources. The Mother-Baby Health Network seeks to strengthen dialogue between communities and facilities to create a sustainable, community-driven demand for accountable maternal and newborn care.

Infant and maternal mortality remain serious public health issues in Kenya, Louis said. The World Health Organization estimates that 77 percent of all maternal deaths occur within the first 48 hours of delivery, and the most recent Kenya Demographic and Health Survey indicates half of the mortality under five years of age now occurs in the first week of life. In the Rift Valley fewer than half of all new mothers receive a postnatal check-up from a health provider, with only 15 percent receiving one within those crucial 48 hours after delivery. Moreover, the proportion of deliveries that occur at a health care facility and with skilled providers in attendance has continued to decline in this region since 1989, with women delivering increasingly in their homes in the presence of a friend, relative or simply alone.

As a result of these trends, maternal mortality remains the leading cause of death among women of child-bearing age in Kenya. United Nations interagency figures indicate that maternal deaths have steadily increased from 380 to 530 per 100,000 live births. This 38 percent increase distinguishes Kenya with one of the highest rates of increase between 1990 and 2008.

“Louis has designed a great project with both a randomized controlled trial and a qualitative component,” said Elizabeth Bradley, a professor at the School of Public Health, director of Yale’s Global Health Leadership Institute, and Fazen’s adviser. “If the mobile phone intervention works, he will also find out a lot about implementation, too — hopefully contributing to the development of best practices in this emerging field.” The other members of the research team are Astrid Christoffersen-Deb, MD, of the University of Toronto; Laura Ruhl, MD, of Indiana University; and Julia Songok, MD, of Moi University in Kenya.

The Grand Challenges grants are highly competitive. From over 600 applicants, 75 finalists were selected to complete the final stage of the Saving Lives at Birth program, and 19 were selected as award recipients. Applications are received from across the globe, including institutional applications from non-profits, faith-based organizations, universities and private enterprises.

— Michael Greenwood (reprinted from Yale Public Health)

Dr Nahida Chakhtoura at St Vincent Hospital

Image

CURRENT JOB OPENING. VOLUNTEER

Image

The Graphic Design Volunteer will assist the lead Graphic Designer in designing both print and digital communications.

Tasks may include but will not be limited to assisting with the design of printed and digital materials.,

Preparing files for print

Strong interest in the non-profit sector and social justice

Adobe Creative Suite (InDesign, Photoshop, and Illustrator

Microsoft Office

Excellent design skills with a strong focus on typography and layout

Excellent communication and organizational skills

Resourcefulness, ability to take initiative, and to work both independently

and as a team

Experience in writing and editing copy for marketing materials

Knowledge of basic HTML and familiarity designing for the web is a plus.