Alma Maseda, 25, is reflected in a mirror in her North Miami home with a book she uses to write her poetry. Maseda will read some of her poems at a literary event on Saturday. Maseda was imprisoned for ten years for the murder of her grandmother and since her release has concentrated on her poetry and school. EMILY MICHOT / MIAMI HERALD STAFF

BY DAVID OVALLE

DOVALLE@MIAMIHERALD.COM

Never forget what it was like to be caged in that forest of lustful, hopeless confusion and rage.

In her dark poetry, Alma Rosa Maseda explores the jagged emotions of her troubled teen years, a creeping sense of loneliness and isolation — and a burst of seemingly inexplicable violence.

Just some of the details of her past — drugs, gangs, mental illness — would weave a complex, painful narrative. But Maseda’s life plumbed depths few young women ever reach.

Just six months months ago, she was released from Homestead Correctional Institution after doing nearly 10 years. For murdering her grandmother in North Miami.

Prison is filled with broken souls. It strips away the societal mask and leaves the anarchist bare, showing the pure hearts of those who shouldn’t be there, as well as the dark hearts of those to whom justice was fair.

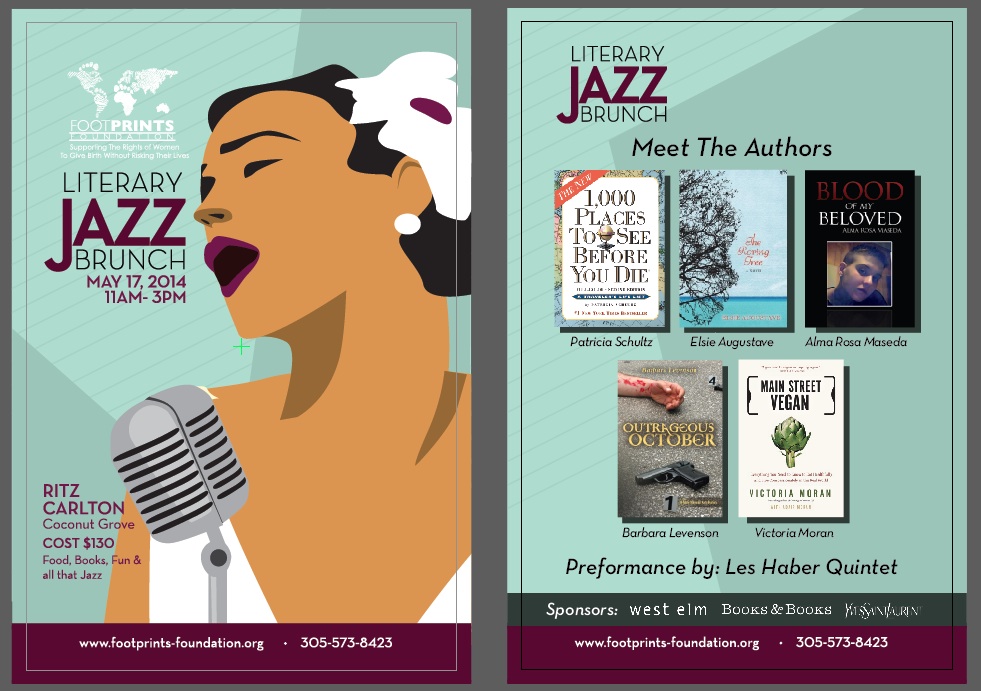

On Saturday, Maseda will join a small group of well-known writers invited to read at a literary brunch at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Coconut Grove — including, ironically, a retired Miami-Dade Circuit judge who now writes murder mysteries.

In her poetry and in person, Maseda does not shy away from her past, nor downplay her culpability in the slaying of her 72-year-old grandmother and namesake. But Maseda, who in addition to writing is studying to be a barber, hopes others will benefit from the story of a broken girl who came of age behind bars.

“My poetry is very personal and it’s very raw,” Maseda said. “Some people, I don’t know how they’re going to take it, but for those people out there who need it, I hope they get whatever it is that they’re searching for.”

Maseda, now 25, lives today in the same North Miami house where she grew up with her father and grandmother, Alma Rosales Maseda. She was 16 when she was arrested.

Slender, her hair cropped short, Maseda could still easily pass for a high school student were it not for a quiet, steely demeanor and weary eyes.

Her mother, who had been addicted to drugs, abandoned the family when she was a small child. While her father worked, she and her grandmother cared for a great-grandmother stricken with Alzheimer’s disease, who later died.

Maseda says she adored her grandmother — “ La luz de mis ojos. The light of my eyes,” she said.

The elder Maseda took her on trips to the toy store, played her Disney movies on the old living room TV and cooked her favorite Cuban dish, saffron-flavored rice with chicken.

Happy memories, oh how you used to smile, stolen by the thief within barbed wire. Too painful to remember, now that you exist alone in a patch of briar.

But as a teenager, Maseda became more withdrawn, even cutting and burning herself. Doctors diagnosed her with bipolar disorder and manic depression.

She began taking the anti-depressant Wellbutrin, which her defense team said could have spurred aggressive behavior. Maseda was kicked out the Lincoln Marti private high school. She enrolled in a school for at-risk children but wound up joining a gang there, bent on embracing a “thug life.”

“I was a ticking time bomb,” Maseda said.

At home, the family also began was falling apart. Her grandmother wallowed in depression, she said, then turned angry when Maseda told her she was bi-sexual. “My house felt like it had a black cloud hanging over it for years,” she said.

The night of the murder haunts Maseda, though she says many details remain murky — along with the reason she did it. Her mind, she says, simply snapped.

She had smoked pot at school early that day, then took a Xanax, the first time she ever took the powerful painkiller. She became so incoherent that her father had to pick her up from school.

Maseda slept it off. That night, her father went out for dinner. Maseda ate with her grandmother, then took her Wellbutrin. Her grandmother took to a rocking chair to watch Wheel of Fortune.

“I even remember the time: 10:35 p.m. But I felt like I was in a dream,” Maseda said. “I had a profound sense of detachment to reality that night.”

Maseda went into to her father’s closet to get his pistol. Hiding it in a stack of mail, Maseda knelt down next to her abuela and embraced her one last time. “I love you,” she whispered.

“No you don’t,” she recalls her grandmother replying.

The words tore at Maseda. In a split second, as though still in a dream, the teenager lifted the gun and shot her grandmother once in the head. Maseda remembers her grandmother looking at peace, a trickle of blood dripping from her nose.

Panic instantly set in. Maseda called the police, but not before turning the gun on herself.

“She shot herself, claiming that a robber had broken into the house and shot her,” recalled her defense lawyer, Lorna Owens.

From there, it all gets fuzzy. But Maseda remembers her dog in the middle of the street staring as the paramedics drove her away in the ambulance.

Maseda soon confessed to North Miami police detectives. Had she gone to trial, Owens would have used an insanity defense, with the claim that the Wellbutrin had contributed to her bizarre behavior.

Instead, Maseda’s father — shattered but forgiving and not wanting to lose his daughter — blessed a plea deal of 10 years behind bars. She entered prison a scared girl.

It’s a place where your personal space is reduced to the top bunk in your cell. Sometimes you’re unlucky and don’t even have a room to escape the hell. You can’t cry because of preying eyes. Chaos reigns to distract from pain.

Not much of a student before prison, Maseda soon began to devour books, everything from the Bible to Anne Rice vampire novels. She also found friendship and eventually love with Diedre Hunt, who is serving a life term for murder.

Hunt urged Maseda to enroll in Art Spring, a creative arts program for inmates at Homestead Correctional.

“Alma was very quiet, very shy, very uncomfortable,” said Leslie Neal, the program’s longtime director. “As she was participating, she slowly came out of her shell.”

Maseda soon penned poems with names like “Lost Innocent,” “Beautiful Misery” and “Magician.”

When she was released in November, she was overwhelmed with emotion when she walked back into the home where the shooting had happened.

But soon, Maseda called Owens. They agreed to have breakfast.

“She said, ‘I have something to show you.’ When she read her poetry to me, the hair on the back of my hand stood up,” Owens said. “They were dark. I found it troubling, but not in a bad way because it’s her story. It didn’t bother me. It was intriguing.”

Owens runs the Footprints Foundation, which works to empower at-risk women. She asked Maseda to read her poetry at Saturday’s literary brunch, which features Patricia Schultz, author of the best-selling1,000 Places to See Before You Die.

Also speaking: retired Miami-Dade Circuit Court Judge Barbara Levenson, who did not preside over Maseda’s case and now writes mystery novels.

One of the poems Maseda will read is called simply “Penitentiary.”

I’ve loved the best. I’ve befriended the worst. I’ve lost myself as well as found, what I’m made of upon this ground.

“This poem was definitely a cathartic experience. It showed me what I went through. It’s like the blood running through your veins,” Maseda said. “You don’t know what it looks like until you actually cut yourself and spill it on a page.”

Read more here: http://www.miamiherald.com/2014/05/16/4120741/after-serving-nearly-10-years.html#storylink=cpy